Her vocal style transports me to the backwoods of Kentucky or West Virginia, delivered fresh and uninhibited, while the live in the studio instrumentation is strictly down home, laid back bluegrass. The songs are backed up by local players Bob Eakle (mandolin and dobro), Lisa Eakle (banjo), with Jessica Cooper on violin, and yours truly adding some overdubs on fiddle, viola, mandola, harmonica, and electric bass.

The basic tracks were recorded by live sound engineer, Chris Bollman, at the unique public recording studio located in the Mesa County Public Library in Junction. I was pleased to be able to mix and master the tracks and produce the final CD. Hidden Canyon is available directly from Tammie, but if you are unable to catch her performances in the area, you can contact Barn Jazz and we can arrange for you to get a copy.

Is Vinyl Better than Digital?

United Record Pressing

- To many it sounds better. If you grew up with it you know THAT sound, and prefer it over the exacting and sometimes overly clinical digital recordings.

- If you did not grow up with it, its a new thing that offers a tangible product, something you can show off if you are in a band. And it sounds better than MP3’s played through ear-buds.

- There is more room for liner notes and info about the band or recording that you can typically get onto a CD jacket.

- It’s cool, trendy.

The downsides:Disc Cutter at Welcome to 1979 studio in Nashville.

RIAA equalization is a little known aspect of vinyl, explained here in a Wikipedia article:

“RIAA equalization is a form of pre-emphasis on recording and de-emphasis on playback. A recording is made with the low frequencies reduced and the high frequencies boosted, and on playback the opposite occurs. The net result is a flat frequency response, but with attenuation of high frequency noise such as hiss and clicks that arise from the recording medium. Reducing the low frequencies also limits the excursions the cutter needs to make when cutting a groove. Groove width is thus reduced, allowing more grooves to fit into a given surface area, permitting longer recording times. This also reduces physical stresses on the stylus which might otherwise cause distortion or groove damage during playback.

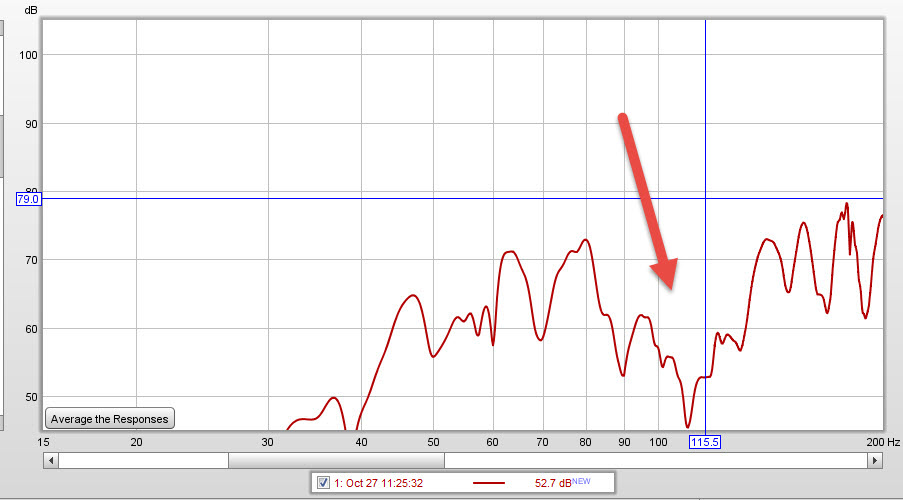

A potential drawback of the system is that rumble from the playback turntable‘s drive mechanism is amplified by the low frequency boost that occurs on playback. Players must therefore be designed to limit rumble, more so than if RIAA equalization did not occur.”

There is an even more “trendy” approach of doing studio recording direct to vinyl, without any digital intervention. That requires taking the stereo mix from the mixer or console, directly to a vinyl cutting machine, in real time. Each master disc costs around $150.00, versus $< $1.00 for a CD. The band has to play perfectly, and there are no re-takes or editing. I would call this “extreme recording”, not for the faint of heart or the lesser of chops.So really the issue comes down not vinyl versus CD, as each has their pros and cons. Unless you really want to spend the extra money, you will stop at the CD level, maybe with some MP3’s thrown in for your web site.

Instead, how can we best integrate analog sound into digital recordings to get the best sound out of digital, regardless if the final product is vinyl or CD? The answer for many audio engineers today is a “hybrid” studio setup, which I have discussed before in an earlier blog post. A professional hybrid setup offers the following:

- Really high quality microphones recording into high quality preamps and other outboard gear such as compressors and EQ’s. Tube preamps are often preferred here, depending on the sound source, voice timbre, etc. The idea here is to capture it in the best analog sound up front.

- High quality analog to digital conversion going into the DAW (Digital Audio Workstation, AKA the computer), so that the sound is not degraded. This is not hard to do these days as the cost of A-D conversion has come down significantly. Some would argue that typical computer sound cards such as the Sound Blaster are sufficient, but I disagree mostly because they are very limited in what they offer for inputs, in addition to having inferior clocking which can influence the sound to a degree.

- Mixing tracks via an outboard analog “mix bus” or chain of, again, high quality tube or solid state EQ’s and compressors before doing one more D-A back into the master stereo track. This involves both analog “summing” of the individual digital tracks using a console or some other outboard device that takes however many tracks are in the recording and sums them down electrically to a stereo master track. Some engineers would say that staying ITB (In the Box, i.e. no round trip to the analog domain during mixing) is better. It really depends on how you work, but I prefer the outboard mixing approach before applying any plugins ITB, if at all. I just prefer what my analog outboard gear brings to the mixing process, and it’s often easier and more consistent than using plugins (albeit more expensive initially).

If the final product will be produced on CD we will master using 24 bit files for headroom. For CD we will need the master to be at the Red Book standard 44.1 KHz sample rate, dithered down to 16 bits as the last step. Often engineers will mix and make the analog round trip at high sample rates such as 96.1 KHz and then down-sample for CD. This requires a very fast computer and lots of disk space, but fortunately that is much easier to obtain these days.If the final product will be on vinyl, an extra mastering step is required to attenuate the extreme highs and lows, as needed, before sending the master disk to the cutting engineer. This takes much skill, and there is a small but growing cadre of young, professional vinyl mastering engineers that are servicing the trendy LP market.

So the take away is, not all digital is created equal! Adding a bit of analog spice makes the final dish taste better, to mix my metaphors (pun intended).