Two months ago I decided I needed a new DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) for my music production. This began a long process, starting with ordering a new hotrod system from Chris Ludwig at FundamentalAV.com. I had worked with Chris 5 years ago when he was with ADK Pro Audio in Kentucky. The new DAW is amazing, incredibly fast, with SSD drives, 11th-gen iCore7 processor, 32 meg. ram, and the most up to date Windows 10 Pro. That was a start.

After another several weeks and considerable labor, I had reinstalled the latest versions of my many audio applications including Cubase 11, Wavelab 10, hundreds of plugins and a raft of virtual instruments. Everything worked perfectly, well mostly everything.

Not being satisfied, naturally, I considered upgrading my monitor speakers. I still have a decent set of Meyer HD-1 main monitors but wanted something more precise for close in, near-field monitoring. I was looking at the higher-end Genelec SAM DSP-powered monitors with room correction, but could not justify the $5000+ cost. Instead I read great reviews for the inexpensive KALI IN-8 MKII studio monitors, at under $900 for the pair! Now these are installed and provide excellent point source imaging and detail. The Meyer’s are aimed more into the room behind my mix position, mainly for clients. The Kali’s I now use for mix decisions and run these at lower volumes. Happiness, until….

I began remixing Less Than Nobody, a song I wrote to support my wife Lynn’s new novel, Measured Time (which mentions a movie titled Less Than Nobody, about the angst of a Vietnam-era vet in a coffee shop, another story for another day). The original version of LTN sounded pretty good but several critical listeners pointed out that, as a rock song, the tempo was not consistent and this got in the way of their enjoyment of the groove. Being mostly an acoustic, free-form player, I had to agree, as I did not record this to a click track. In fact when I sent the song off to a drummer who, for $100, would record a great drum part, he declined after listening to it, saying, “was this not recorded to a click? I can’t work with this…” – Well, phooey!

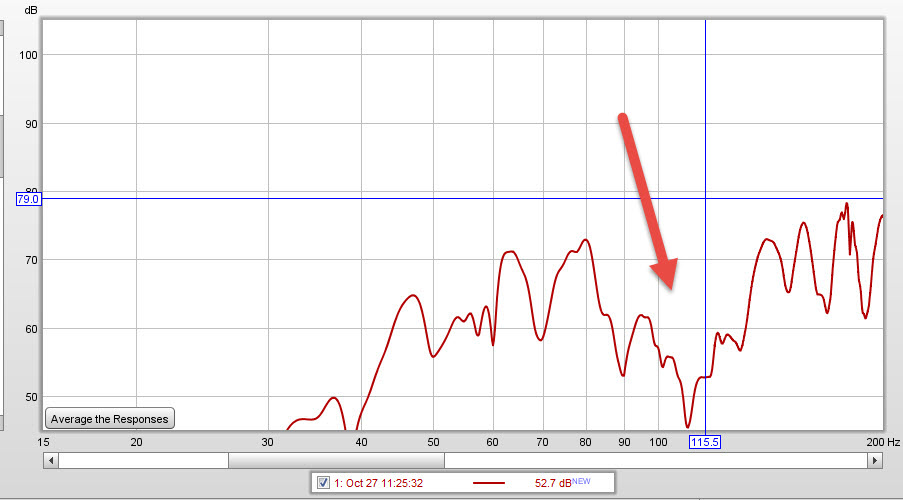

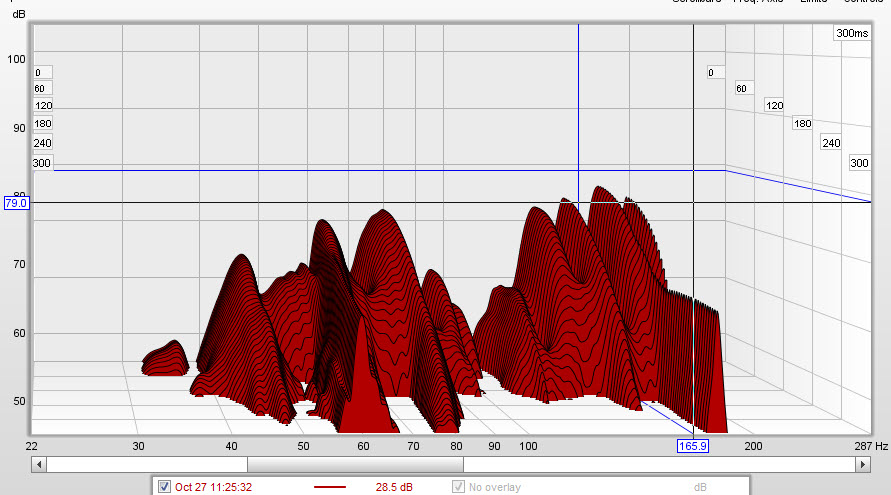

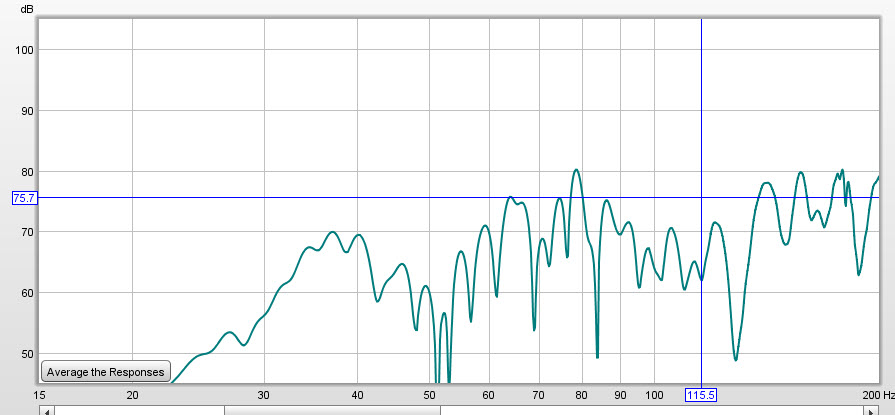

Listening with my newly acquired precision monitors, I had to agree that if I am going to do a rock song, a consistent tempo would be a necessity. I pulled up the Cubase project from a year ago, and began re-recording the guitar and bass parts, while listening to a click track in the headphones. I added more consistent drum grooves using BFD3. It was sounding more like a proper rock song, except for….. what’s that? Distortion? No matter how I adjusted the mix, the newly recorded tracks exhibited mild to annoying levels of nasty distortion, mainly when the bass or vocal tracks were playing. The wave forms did not look clipped, and in fact I had used conservative levels when recording the mic’d up amp.

I started to think I had made a mistake with the Kali’s, because being so inexpensive, could they be faulty? Could they not handle the levels (not very loud) that I was sending. Or was there an issue with room resonance? Or my recording technique? This bugged me for several weeks. Friends who came over to listen noticed the problem as well, not only in this but in other songs. Bummer!

Finally I stopped thinking about all of the new gear and what might be wrong with it, and thought about my signal chain. I knew from past experience that good sound was all about gain staging, making sure nothing was overly loud or even clipping. What I was hearing did sound like digital clipping. Fortunately I have some really nice Dorrough analog loudness meters that show the level that is actually going to the monitors, as opposed to the digital level meters in Cubase, which showed nominal levels. What could I have overlooked?

Max Headroom! – Or rather, NO HEADROOM. I opened the Lynx mixer application that stands between the output of Cubase and the input to my digital to analog convertors, part of the signal chain the feeds the speakers. All of the faders in this innocuous, mostly out of sight application, were set to max! Yikes, no wonder the Dorroughs were pegging into the red! How could I have overlooked them?

Maybe because I was focusing on the metering and waveforms in the DAW’s UI and not the entire signal chain. Maybe because I was having second thoughts on the recent purchases, or the several grand spent on a new computer. I fact, I was missing the most obvious and fundamental part of my setup – the gain staging of the entire signal chain.

Turning down the faders on the Lynx Mixer by 10 dB restored the headroom that I used to have before I embarked on setting up this new system.

LESSON LEARNED – Less Than Nobody (V.2) is finally sounding like something somebody will want to hear! Stay tuned for a new Soundcloud link.

Is Vinyl Better than Digital?

United Record Pressing

- To many it sounds better. If you grew up with it you know THAT sound, and prefer it over the exacting and sometimes overly clinical digital recordings.

- If you did not grow up with it, its a new thing that offers a tangible product, something you can show off if you are in a band. And it sounds better than MP3’s played through ear-buds.

- There is more room for liner notes and info about the band or recording that you can typically get onto a CD jacket.

- It’s cool, trendy.

The downsides:Disc Cutter at Welcome to 1979 studio in Nashville.

RIAA equalization is a little known aspect of vinyl, explained here in a Wikipedia article:

“RIAA equalization is a form of pre-emphasis on recording and de-emphasis on playback. A recording is made with the low frequencies reduced and the high frequencies boosted, and on playback the opposite occurs. The net result is a flat frequency response, but with attenuation of high frequency noise such as hiss and clicks that arise from the recording medium. Reducing the low frequencies also limits the excursions the cutter needs to make when cutting a groove. Groove width is thus reduced, allowing more grooves to fit into a given surface area, permitting longer recording times. This also reduces physical stresses on the stylus which might otherwise cause distortion or groove damage during playback.

A potential drawback of the system is that rumble from the playback turntable‘s drive mechanism is amplified by the low frequency boost that occurs on playback. Players must therefore be designed to limit rumble, more so than if RIAA equalization did not occur.”

There is an even more “trendy” approach of doing studio recording direct to vinyl, without any digital intervention. That requires taking the stereo mix from the mixer or console, directly to a vinyl cutting machine, in real time. Each master disc costs around $150.00, versus $< $1.00 for a CD. The band has to play perfectly, and there are no re-takes or editing. I would call this “extreme recording”, not for the faint of heart or the lesser of chops.So really the issue comes down not vinyl versus CD, as each has their pros and cons. Unless you really want to spend the extra money, you will stop at the CD level, maybe with some MP3’s thrown in for your web site.

Instead, how can we best integrate analog sound into digital recordings to get the best sound out of digital, regardless if the final product is vinyl or CD? The answer for many audio engineers today is a “hybrid” studio setup, which I have discussed before in an earlier blog post. A professional hybrid setup offers the following:

- Really high quality microphones recording into high quality preamps and other outboard gear such as compressors and EQ’s. Tube preamps are often preferred here, depending on the sound source, voice timbre, etc. The idea here is to capture it in the best analog sound up front.

- High quality analog to digital conversion going into the DAW (Digital Audio Workstation, AKA the computer), so that the sound is not degraded. This is not hard to do these days as the cost of A-D conversion has come down significantly. Some would argue that typical computer sound cards such as the Sound Blaster are sufficient, but I disagree mostly because they are very limited in what they offer for inputs, in addition to having inferior clocking which can influence the sound to a degree.

- Mixing tracks via an outboard analog “mix bus” or chain of, again, high quality tube or solid state EQ’s and compressors before doing one more D-A back into the master stereo track. This involves both analog “summing” of the individual digital tracks using a console or some other outboard device that takes however many tracks are in the recording and sums them down electrically to a stereo master track. Some engineers would say that staying ITB (In the Box, i.e. no round trip to the analog domain during mixing) is better. It really depends on how you work, but I prefer the outboard mixing approach before applying any plugins ITB, if at all. I just prefer what my analog outboard gear brings to the mixing process, and it’s often easier and more consistent than using plugins (albeit more expensive initially).

If the final product will be produced on CD we will master using 24 bit files for headroom. For CD we will need the master to be at the Red Book standard 44.1 KHz sample rate, dithered down to 16 bits as the last step. Often engineers will mix and make the analog round trip at high sample rates such as 96.1 KHz and then down-sample for CD. This requires a very fast computer and lots of disk space, but fortunately that is much easier to obtain these days.If the final product will be on vinyl, an extra mastering step is required to attenuate the extreme highs and lows, as needed, before sending the master disk to the cutting engineer. This takes much skill, and there is a small but growing cadre of young, professional vinyl mastering engineers that are servicing the trendy LP market.

So the take away is, not all digital is created equal! Adding a bit of analog spice makes the final dish taste better, to mix my metaphors (pun intended).